The Power Of Restoration

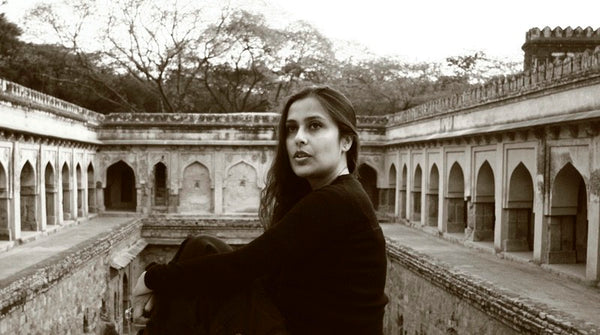

When it comes to conversation architecture, only one name comes to mind–Abha Narain Lambah. In her expansive career over several decades, she’s worked on some of the most magical projects in architectural history. We spoke to the woman behind the award winning firm to understand her craft in detail.

What made you consider a career as a conservation architect?

I feel that the conversation around sustainability has become louder. But when I graduated, 30 years ago, I was very conscious that I didn’t want to add to the urban chaos unless I had something to contribute positively. I’d rather conserve buildings that are really iconic and that to me is the greenest building. So it’s recycling buildings, for me, rather than you know recycling paper or water. Construction is one of the most energy-consuming and polluting industries that there is. So, I think there is this consciousness that I had right from the beginning of my career.

We are also working with new build in projects like the Raj Bhavan, the Gateway of India and Balasaheb Thackeray's Memorial. At every point we ask the same question–even in new build–are we improving the urban cityscape or are we cluttering it? I think that’s been a very important question we’ve asked ourselves right through the 25 years of my practice.

How do you choose projects?

Sometimes the project finds me and sometimes I find the project. Projects like Dadabhai Naoroji road, my work with the streetscaping way back in ‘98 was because it bothered me every time I walked down the road and couldn’t even see the buildings because they were completely plastered over with sign boards. I mean I was so committed to making a change that I went and approached MMRDA and made these guidelines. Even though my architectural scope was over I continued to convince the local stakeholders and the shopkeepers to implement those signage relocations. So I think throughout it is more the empathy with the project or the site that becomes the project even if there’s no client, there’s no brief or client, like in a very traditional project where you have a client and they pay you and you do your job and that’s about it.

What were some of your early influences in life? What drew you to architecture?

Throughout my childhood, I’ve had really diverse experiences. I was born in Calcutta and my earliest memories of visiting Shanti Niketan and Victoria Memorial at the age of three. Life comes in full circle–I’ve worked on the nomination of Shanti Niketan and it being declared a World Heritage Site. In my early teens, I was a student cycling down Chandigarh completely inspired by Corbusier’s work. Modernism came early in my life when I was very influenced by Corbusier’s architecture and I had the opportunity to work on creating the management plan for the UNESCO site of the Capitol Complex many many many years later in 2017.

When moved to Delhi spent a lot of time walking around the ruins of Mehrauli and South Delhi and I think that also led me to conservation. In Delhi what really led me to architecture even before that was I walked in once to the India Habitat Center I was just so amazed at how Stein as an architect was contemporary and yet so respectful to the past that I just made up my mind that I am going to study architecture and join his firm and then went on to be the last architect to be hired by him. So yeah, life has been very strange you know, some incidents did happen very early on they just came full circle after 30 - 40 years.

Your line of work needs immense patience–the persevering of original materials, and retaining character in pieces. How do you see potential in things others don’t?

I think I am rather spontaneous and my friends or family will say I am rather impatient. But when it comes to my work I am just the opposite with my work–I have once waited for 17 years for a project to begin. We were appointed to work on the Crawford Market in 2007 and had to battle a whole lot of builders, and pressure… and our project with the holistic redevelopment is due to be completed in 2025.

I think with public spaces, you have to wait for the project to be completed for years for the vision to come alive but you have to be this persevering because if I didn’t do that, it’d never happen. You win battles, you lose battles sometimes it’s like snakes and ladders–you move two steps and then one change of policy and then everything comes crashing down.

What is your advice to those seeking help in conserving heritage structures they may have inherited?

My advice would be first let’s say congratulations, you’re lucky enough to inherit a historic building and you should be very very privileged it may seem like a drain on your resources but it’s a major asset and people who know how to treat it like an asset, manage to make it financially viable and those you treat it like a liability that’s a different story. So, I feel your approach to a heritage building is the key to this entire equation. For example, when the Opera House owners had locked it up for 25 years it had not been put to use and it was bleeding money, we took a leap of faith and I am just so grateful to my clients, they just put their faith in me. I think very often it’s your approach as an owner that really makes the difference.

You’ve worked on restoring some iconic spaces. Which has been the most satisfying project for you to date?

For me, it’s painful when I go back to a project almost after years and find that it’s not been looked after. But every time I go back to a building where it’s been looked after, it’s been attended to, it’s been reused by the public and enjoyed that gives me the most pleasure.